Sometimes, and I’d say rarely and therefore magically, we read books that speak to us like friends. Their authors and us are kept up at night by the same questions. Our hearts pitter-patter to the same hum-drum. Such authors offer a translation of thoughts we ourselves haven’t found words for. They clear a path down stories that aren’t our own, down thoughts we have yet to explore.

Timing matters.

Timing matters.

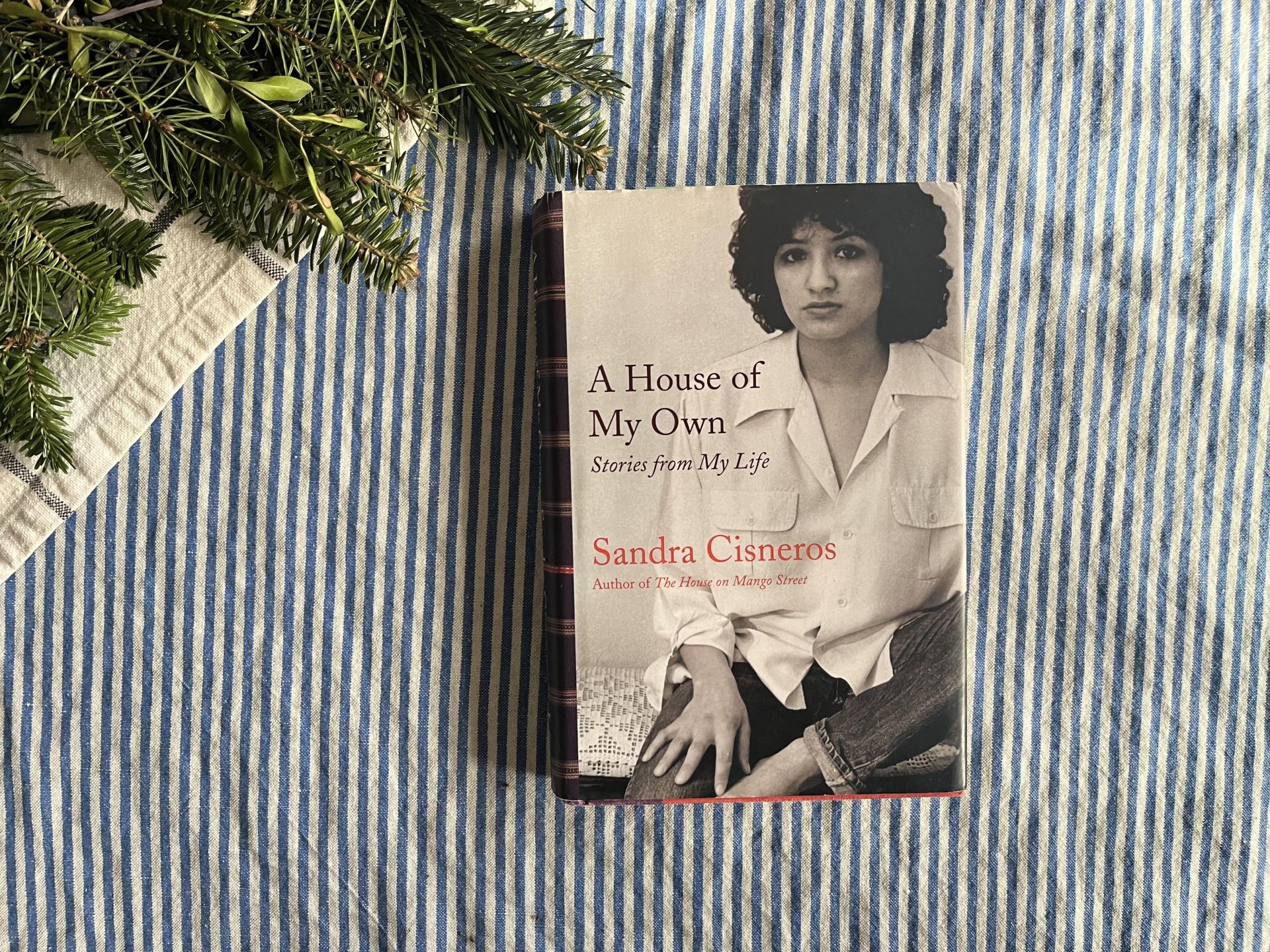

I found A House of My Own in the midst of my MFA Writing Program.

"When I recognized the places where I departed from my neighbors, my classmates, my family, my town, my brothers, when I discovered what I knew that no one else in the room knew, and spoke it in a voice that was my own voice, the voice I used when I was sitting in the kitchen, dressed in my pajamas, talking over a table littered with cups and dishes, when I could give myself permission to speak from that intimate space, then I could talk and sound like myself."

Voice is a thing of courage.

“It was always the “how” and not the “what” we talked about in class. Even while I was teaching in the Chicano community, the two halves of my life were at odds with each other—the half that wanted to roll up my sleeves and do something for the community, and the half that wanted to retreat to my kitchen and write.”

Writing, while initially a solitary act, is also communal.

One professor of mine enjoyed spending time with material that was difficult.

“She doesn’t want to write a book that a reader won’t understand and would feel ashamed for not understanding.”

and

“She thinks people who are busy working for a living deserve beautiful little stories.”

"How can art make a difference in the world?"

“I don’t know anything, but I know this: whatever is done with love, in the name of others, without self-gain, whatever is done with heart on behalf of someone or something, be it a child, animal, vegetable, rock, person, cloud, whatever we make with complete humility, will always come out beautifully.”

an mfa isn't the only way to grow as a writer